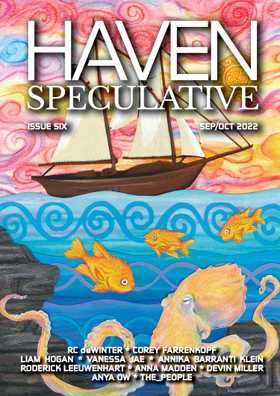

FICTION

Sharing a Meal at the End of the World

by Anya Ow in Issue Six, September 2022

Sometime after the end of the world, a man buys a woman a drink.

He’s old enough to remember a time when drinks at no-name bars like this one came in bottles with printed labels, made in everywhere—glass bottle in Australia, label in China, hops in America—the casual wealth of easy resources bottled up for cheap. She isn’t. Maybe that’s the draw for them both.

“Samuel,” he says, when she takes a seat at the table. “Sara, yah?”

Sara nods. “Hi Samuel. Nice to meet you.” She attempts a smile. It’s been a while since she’d last had the resources to go on a proper date, so she’s splurged. Mineral powder makeup, the last of her blusher, even some lipstick. Samuel’s possibly worth it, judging by his Bumblr profile. He’s tall, an atheist, has a full-time job and Grade+ access to water rations, which more than makes up for his average access to everything else.

Samuel smiles. He’s nervous and it’s obvious why, He’s grown out his hair and tried combing the worst of it over the scars. A quarter of his face and most of his right arm are puckered with pink-grey whorls, the mark of a NCB2 virus survivor. Not that Sara minds, but people born pre-Outbreak, like Samuel, have funny hang-ups about scars. “One good thing about the apocalypse,” he says, looking her over, “is that I prefer women without makeup.”

It’s all Sara can do not to roll her eyes. Men. She fakes a laugh instead and hides her irritation by attracting the attention of one of the staff. She’s out of practice and hopes it doesn’t show. They order the housemade moonshine, or try to. The waiter taps the matte black cuff around his wrist apologetically. “That’s half a water credit.”

“Half?” Half a credit is a quarter of a day’s worth of drinking water, and Sara straightens, about to suggest that they go elsewhere, but Samuel leans over and taps his own ID cuff against the waiter’s. There’s a faint ping and the waiter nods, backing off under her unblinking stare.

“You didn’t have to,” Sara says, now uncomfortable. She’s always uncomfortable when guys insist on paying for a date. It tends to give them certain expectations of how the date’s meant to end, which can get messy. Sara fiddles with the edge of her slimweave dress under the table. It’s the only thing she owns without adthread woven into the sleeves and back, but now she wonders if it’s giving Samuel the wrong idea about her income level. There’s only one other person in the bar without adthread, and they’re sitting at the far corner of the bar by themself. Even Samuel has adbars on both his sleeves, winking up silent graphics every six seconds about the latest soyprot printer.

“I picked the bar, so I should pay,” Samuel said. Nice and casual. It’s hard to tell what anyone really feels outside of a Whatslink hookup, but Sara works in marketing. She’s comfortable both online and inflesh, comfortable with fakery. Sara tries another smile and picks up the menu. It’s not actually made of real paper—there isn’t enough water or arable land left in the world for that—but it’s a fine mimicry.

“Steak? Really?”

Samuel laughs. It’s a weird sound, more like a strangled bark. Still nervous, maybe. Or equally uncomfortable. Chemistry—that’s what pre-Outbreak society used to describe the degrees of comfort between people inflesh. They’re two substances that have pushed themselves into contact, not knowing whether the other was inert or volatile or just mediocre, both of them infected by the impurities of awkward circumstance. “It’s not the real thing, not for that price.”

“Have you eaten cow before? I mean, beef?” Sara blushes a little, embarrassed by her slip. It’s betrayed her age.

“Well, yes.” Now Samuel is definitely being condescending, smiling broadly. Sara relaxes. Condescending men are easier to handle. It’s nothing new—especially in modern marketing. “Jesus, I’m not that much older than you. Am I?”

“About twenty years, I think.”

“Damn, now I’m feeling old.” He winks, and it looks like a bad tic inflesh, like an invisible hand scrunching part of his face into a brief fist. Sara manages not to grimace. Emogines are so much cleaner. “Yah, when I was growing up, you could still get beef. Plus bread, chocolates, vegetables, fruits, coffee—anything you could think of, sold in big stores. Physical buildings, not this online delivery stuff that everyone does now. You could walk in and pick what you wanted.”

Sara nods. Everyone knows this, but it’s still comforting to hear, one of the few comforts left from strangers of Samuel’s age. It’s one of the reasons why she still matches with them on Bumblr. “I was born the year after the Outbreak.”

“Year One? Shit. You’re lucky to be here.”

“I know.” The drinks arrive, and the moonshine’s a touch too strong, but it’s the first alcohol Sara’s had in a month, so she sips it gratefully, lets it burn on the way down. They order food, not that Sara thinks the soyprot printer in a bar like this could manage anything better than uneven protein chunks.

“I remember the Outbreak.” Samuel glances away, at the door. “I was in uni. Saw the news when I was studying for an exam. Wasn’t much at the start. Just the announcement of some ancient super virus infecting people far north, released from melting permafrost. Didn’t think it’d spread so quickly. Nobody did.”

“You survived.” It’s a vacuous thing to say, with Samuel’s scars, but Sara doesn’t mean it that way. Awkwardly, she adds, “So did my mum. Rest of my fam wasn’t lucky. Dad caught a late strain. Before the vaccine.”

“Sorry to hear.”

“Hai, I didn’t know him, wasn’t even a year old when he passed. I’m sorry to unload. Hope you don’t think it’s creepy.”

“Not at all.” Samuel’s tense. He’s a bad liar, but everyone lies now. How’s things? Good, you? She doesn’t take it personally. Modern dating is impersonal by nature, a slot machine of tedious answers geared towards a generally bad result. Outside, heavy rain blots the dim lights of the neighbouring shophouse block into fluorescent pink and purple blurs.

The soyprot food comes at last, and it’s not as bad as Sara thought it would be, deep fried chunks with soyprinted eggs. There’s even some faux spring onion in acid green shades. Samuel savours each mouthful, chewing slowly, and he blushes as he notices her stare. “Reminds me of something from before,” he explains. “Chai tow kueh. Fried carrot cake with egg, except it wasn’t made with carrots but with radishes.”

“Was that your favourite thing to eat? From before the Outbreak?”

“Chicken rice. That was my favourite thing. Cooked with ginger and broth. You eat it with dark sauce, ginger sauce, and chilli.” Samuel talks wistfully as they pick over soyprot and finish the moonshine. She knows what chicken rice is, of course. It was the favourite thing of one of the guys she dated a month ago, too, and one of the women from before that. Tedious. Maybe Samuel isn’t going to be worth the effort. Sara listens, losing interest, until Samuel says, “But the thing I miss most? My grandmother’s braised duck.”

“Like duck rice?” Someone had told her about duck rice. She doesn’t remember who, now.

“Something like that. But it’s a labour of love. After you clean the duck, you fill it with water chestnuts, then you sew it up and deep fry it whole in a wok. Five spice powder, palm sugar, dark and light soy sauce, cinnamon, star anise, cloves, water, and braise it for a few hours until the meat falls off the bone. There’s nothing like it.” Samuel’s eyes are misting over. For a moment, even without emogines, Sara can share it. She can even taste the oily-sweet-salty meat of the duck, slippery and soft over her tongue. Yes, she decides. Sara smiles. Avarice has always made her attentive.

After drinks, they step outside. Raindrops are still thundering down through the sticky heat, the water now knee-deep. The bar and its neighbours keep the floodwater out using collapsible KeepDry, a foldable stepway that seals upwards against the door. It’s transparent and lined with adthread, graphics about the very latest in KeepDry tech lighting up under their feet as they climb up onto a floating platform flush against the bar. Debris floats past, bumping against money-back guarantees: a plastic bottle, a muddy shoe. So much chemical water, all undrinkable. The drowning world smells of rot and mud and Samuel’s cheap cologne.

“You like talking about food,” Samuel says, as they call for an amphiber. “Are you a foodie? That’s rare nowadays.”

“I guess I am,” Sara says, though the word doesn’t feel right to her. Or the weird curl to Samuel’s mouth. Condescension again. “I love cooking, too.”

“Cooking what? Soyprot stuff?”

“I make do, yes.”

“I like that in a woman. Being able to cook. Means you’ve got some traditional values.”

Sara looks away down the street, pretending to be distracted by a passing amphiber so she doesn’t have to smile. “Thanks.”

“Isn’t it sad? Talking about things that you’d never be able to eat.”

“No sadder than all this.” Sara nods at the rain. “Food is such a core part of any human culture, and we’ve lost it. Everywhere in the world. Everyone eats the same thing now. Anyone still alive, that is.” The Outbreak cut the global population in half. Maybe more. Most of the northern hemisphere is empty land now, going fallow. NCB2 didn’t spread as virulently in the tropics as it did in the cold.

“It’s not so bad here. We don’t get wildfires or tropical storms. We’ve replaced the streets with materials that won’t melt during the day. Raised our shoreline against the sea level. Technology will keep getting better. Things will make a comeback.”

“With everything extinct?”

“Not everything’s extinct.” Samuel tentatively tries to grasp her hand, but Sara quickly pulls away. Samuel’s hand freezes awkwardly in mid-air before falling back to his side. “Humans are still here. The government will fix things.”

“We’ll see.”

“You vote Opposition?”

“Does it matter?” The ruling party of Singapore had been in power now for over a century, consistently winning majorities in all of the districts but one. Hers.

“So, you do,” Samuel says, smiling. It’s not a kindly smile. “Young people. I was like that once. Voted for the Worker’s Party. That’s what SGFirst used to be called. Then you grow older and realize that a stable government isn’t so bad. Look at our neighbours. Besides, SGFirst is anti-immigration.”

“My mum votes ruling party too. Older people, huh?” She says it to be cruel—when she votes, she votes indifferently. Both parties are the same to her. Samuel stiffens a little, looks away. When the amphiber comes, he wishes her good night, and leans in to peck her on the cheek.

Sara presses her fingernails against his jaw, jabbing with the sharpened tip of her index finger. This part is always tricky. Samuel blinks at her, his mouth opening and closing. He staggers back, but Sara manages to steady him before he falls into the floodwater. The fast-acting anaesthetic takes effect in degrees, making him slump against her as she manhandles him into the back seat. She runs her fingertips against the adbars on his sleeves in a precise pattern, shutting them off. No adthread, no geolocation.

Once Samuel is settled in, Sara ducks into the front passenger seat. “Farthing Street 75394,” she tells the amphiber, humming as it navigates itself down the river-street. Sara doesn’t look back. There’s nothing to see.

The Aljunied sector is minimally lit. Generations of being punished with low resource allocation for voting Opposition makes itself obvious in the district’s unpainted blocks of crumbling flats, their solar plating years out of date. The banks of street lamps describe shadows over closed shops barred up with sandbags and old KeepDrys, no personal amphibers tethered nearby. An amphibus cruises past, empty but for a woman and a boy near the back, faces wrapped in filtermasks. Adthread activates against the amphibus’ flanks, overlaying them with a garish cloud of purple letters.

A guy sends Sara a message on Bumblr as she climbs out of the amphiber and onto a floating platform. How was her day, blah, what is she doing now? She ignores it as she hauls Samuel out onto the platform, grunting with the effort, slipping twice on the gravmat. She swipes the amphiber credit for the ride and it leaves, but she waits till she can no longer see it through the rain before unmooring the floating platform and reaching under it for the attached pole. Her dress is soaked now, plastered to her skin as she poles them away from the street to the awning at the back of an abandoned warehouse down a service access lane.

She beaches the platform on the loading bay slope of the warehouse and kicks off her heels, pulling on rubber boots as hover rigs drag the floating platform with Samuel’s body up to her workspace, set up in a dry corner inside. A heavy cleaver has pride of place on a wall with brackets of tools, and she runs her fingertips over its steel handle lovingly before heading to the soyprot printer to input personalised food printing codes that she scours off specialised databases.

Dark and light soy sauce. Cloves and star anise. Cinnamon sticks, water chestnuts.

None of it will taste much like the original, probably, but it isn’t as though she has a frame of reference for her regrets. Sara uses the last of the day’s water credits to fill a large pot, setting it to boil.

Samuel wakes screaming when she makes the first cut, but tied down, his pain doesn’t matter. This is a labour of love.

© 2022 Anya Ow

Anya Ow

Anya Ow is the author of Ion Curtain, The Firebird's Tale and Cradle and Grave, and is an Aurealis Awards finalist. Her short stories have appeared in Asimov's, Uncanny, Fantasy Magazine, The Year's Best Dark Fantasy and Horror, 2019 anthology and more. Born in Singapore, Anya has a Bachelor of Laws from Melbourne University and a Bachelor of Applied Design from Billy Blue College of Design. She lives in Melbourne with her two cats, working as a graphic designer, illustrator, and chief studio dog briber for a creative agency. She can be found at anyasy.com or on twitter @anyasy.