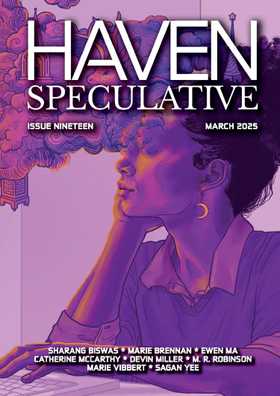

FICTION

A True Account of a Pre-Teen Blob

by Marie Vibbert in Issue Nineteen, March 2025

5068 words

Milly and I walked home from school to find Mom sitting on the porch with her suitcase on her lap. She turned away from us and shouted into the door, "They're here. Move it!"

Our older sister, Becky, slouched out in barely obedient teen anger, a beach tote on one shoulder and a plastic grocery bag in her other hand.

"Leave your schoolbooks," Mom said, standing. "Let's go."

There was a strange woman in our driveway, in a brown pencil skirt waiting by the door of a strange brown Buick. She was brown, too. I admired the color-coordination.

"Move," Mom pulled the air as if to tug us along. "We've been waiting while you two dawdled."

I dropped my stack of books inside the door, but Milly only left her Trapper-Keeper, holding tight to her pleasure reading, a nearly cube-shaped paperback edition of The Gulag Archipelago.

The brown car had a foreign cleanness, sealed against the wind in a way we weren't used to. We went up on the freeway and houses glided by from a new angle. I imagined it was like being in an airplane.

Mom looked back at us from the front seat with maniacal glee. "We're going to the Battered Women's Shelter!"

She said it with definite capitals, like it was an accomplishment, like we were going to Harvard, maybe. I didn't feel battered. No one hit us other than Mom, or Becky. Or that boy down the block. No one hit Mom or Becky but each other.

So okay, there was a lot of hitting, but it was normal hitting. We didn't have broken arms or black eyes. All I had was a bruise on my left ankle, just to the front of the bony protrusion on the side. Bodies bruised because the world was hard and had rough edges and bones got in the way. I wished my whole body would bruise. I could roll like a meatball off the car seat, out the door and down the highway. I could be a wonderful monster.

"We're never going back," Mom added, joyful and sadistic.

Milly gripped her book tighter against her flat chest. We never knew when the horrible things Mom said would be true.

#

The shelter was called Westfield House, and it was in Erie, an hour's drive from the podunk town we lived in. We'd been to Erie before, the good parts like Waldermere Amusement Park and Burger King, but we'd never noticed Westfield House nestled in an unassuming row of homes turned into daycares and antique shops. It was a soot-stained brick Victorian with one of those tall doors and a little fence on the roof called a Widow's Walk. It didn't have a sign. The windows were flat black, like there was nothing inside and they'd forgotten how to reflect.

Everything inside was bare, like a museum between exhibits, and the dozen women who lived there all crept and whispered like they were trespassing, like the original owners of the house were still here as ghosts, and no one wanted to bother them.

The brown woman looked from Mom's bag to Becky's and back. "Do you have a bag for the twins?"

Mom turned to Becky. "I told you to pack a bag for the girls!"

Becky's look was thunderous. "You did not."

With a heavy sigh, we were led to a storeroom full of boxes of donated clothes. We each got a brand-new toothbrush in crinkly plastic, and a tomato-soup-red dress for me, brown corduroys for Milly. I could tell the lady watching us make our selections had hoped these things would go to better kids.

But now we would be better kids. We would be like the protagonists in an orphanage book. I already felt quieter, more thoughtful. Maybe I'd take up needlepoint?

The upstairs hall had a giant hole in it for the stairs and a railing all around, like a balcony. I squealed and raced around. "No running in the hall," the woman said. "No running at all!"

There was a round armchair tucked in this nice little corner of the balcony by a big window that looked out at the front yard. I snuggled into it, and the woman grabbed my arm and tugged me up. "That's for nursing mothers, only."

She showed us into a yellow room with slanted walls. Out the window I saw a swing set. "Can we go out and play?"

"No one is allowed outside, and no one is allowed on that swing set. We have to maintain secrecy. Try to avoid standing in the windows."

This was not the magical experience I had been hoping for. The woman took us to the "back parlor" and said we were allowed to play in there. There was no TV. No radio. There was a door into the Front Parlor, which looked just lovely with plastic-covered floral sofas and a fireplace. I tried to sneak in twice. A younger woman would run from the office across the hall in seconds. She had to have an alarm or something.

All the back parlor had was a box of baby toys and a shelf of baby books. Not even good baby books, educational ones like "Everybody Poops."

I sat on the window seat, pressing my thumb into the bruise on my ankle, watching the color bleed and pop back. I'd been working on it. I'd managed to get it almost double its size, and the center had a pleasing puffiness, but as an entertainment option, it was getting old.

Milly was on her stomach on the floor, intent on her book.

"What's The Gulag Archipelago?" I asked.

She drew the wet, needle-like point of hair she'd been sucking on out of her mouth. "It's a chain of islands where the story takes place."

"No, I mean, what's it about?"

"It's a true account of being tortured." She pressed her nose closer to the pages.

Why hadn't I grabbed a book? We'd been in a silent competition to read the longest book for our fifth-grade reading reports. I'd thought I'd won by a landslide with David Copperfield, but then Milly found that island-themed doorstop, presumably in a treasure chest buried in a fairy circle.

"Can I read it for a bit?"

"No."

I laid down crosswise from Milly and tried to read the back cover. She got up and moved to the piano.

"Come on! If you let me read some, we could talk about it."

Milly chewed her lower lip, but after a moment she buried her nose again. "When I'm done," she said.

If I'd had paper and a pen, I could have started my own true account of being tortured.

The only other kid at the shelter was poking through the baby books. She was maybe a year or two older than us, and dangerous looking, with leathery hair that hung in her face. She noticed me staring and jerked her head right. "Do you want to get out of here?"

"Me?"

She nodded. I looked over to where Milly was reading on the piano bench. The silvery upright piano had a paper sign taped where music would normally sit that said, "do not play the piano." The keys were yellowed wood textured with dried glue. Someone had taken the ivory to sell before donating it.

I looked back at the girl, who was tapping her foot. "Just me?" It was the first time anyone had suggested I do something without my twin sister.

She frowned at Milly and seemed to grasp my anxiety. She nodded. "Come on." Perhaps this girl sensed something in me, something of the rebel soul, the leather jacket I imagined owning one day.

We went into the kitchen with its cupboards taller than stepladders. A woman was editing the chore chart on the wall. We pretended to read it until she left, then we made our break.

The back porch was tall and wooden, white with brown leaves scuttling over it. I wanted to admire it, to squat below the railing and feel myself swing over the edge, but she vaulted the steps and waved frantically at me, "Come on! We'll get caught!"

We crouched low and ran along the hedges until the house was out of sight and we could discover all the entertainment two kids with no money could find in Erie, Pennsylvania, on a weekday.

"I'm Kimber," she said, easy, like we'd been friends all along.

Just around the corner was a library. It was a Brutalist cement block, all beige right angles, a giant slab of an overhang shadowing the stairs. Inside, though, it smelled like any library, like books and crinkly plastic covers and wood polish.

Kimber perused the magazines. I found the science fiction by instinct. Four sections of half-height shelves stuffed with paperbacks bearing little rocketship stickers on the spines. I salivated. My fingers itched. Where to, first? Something with Amazons? Robots? Amazon robots?

A thought hit me like a heavy sack of laundry. My library card was not for this library, and I didn't even have it on me.

The world was exquisitely subtle in its tortures.

Kimber did not look like the sort who would agree to wait an hour or two while I read something. Still, I picked a book with stars and chrome lettering and carried it with me, looking for a secluded place to read.

A scintillating light wavered around a plain wood door with one of those library kick-stools propping it open. Once, Mom had taken us downtown late at night and we'd broken into a hotel. The swimming pool was lit from underneath, and it moved like a living thing, quivering, more solid than mere water. This light was like that, turning the institutional beige metal into something ethereal.

My despair vanished. I was certain I was about to find a gateway to Narnia. The watery light was accompanied by watery voices, talking in strange cadence, indistinct, like the amplified drip sound effect that alerted the viewing audience that the plastic-draped set was meant to be a cave. Or it was ghosts. Alien ghosts.

The door opened on the top of a staircase. Creeping down those stairs felt like swimming into a well; the air itself felt thicker, saturated. It was darker at the bottom of the stairs, the play of light clearer, dancing magic along the floor and ceiling.

It was a cafeteria-sized room. Not Narnia. (Was it ever going to be Narnia?)

A movie projector crouched on a tin cart like a mechanical insect, ticking furiously to itself. In front of it were rows of folding chairs with "ECPL" stenciled on the back, the farthest of which had people in them—older, lumpish people.

And there, on the screen, was a glorious revelation. I stopped trying to catch the secret way the projector ate the film and spat it out again. I stopped trying to pronounce "ECPL." I stopped breathing.

The movie screen rippled with a breeze, floating just above the wall, and on it a great gelatinous mass squeezed through the tiny doors of a toy movie theatre, popping the front off a ticket booth. The camera cut to a woman who squeezed the sides of her head, screaming like she had invented sound itself and intended to use every last bit of it.

The glistening mass juddered forward through miniature sets, flickering into color now and then like two realities interposing. The world was thin and the raw edge of it was in front of me.

Something brushed my arm. I flinched, my heart catching in my throat.

It was Kimber. "Come on, I'm bored."

"Shush!" I pointed at the screen. Military men talked at each other like they were holding their faces on with a button clenched in their teeth.

"This is a stupid old movie. I've seen it," Kimber said.

I was desperate for the boring men to leave the screen so we could get back to the goo part. The reality-tearing part. Kimber pulled my arm until my shoes squeaked on the linoleum. "Come ON, or I'll leave you here for the authorities!"

I left with tears wetting my cheeks, never knowing if the lovely blob got to eat the tight-lipped men, but even at my age, I knew better than to tangle with The Authorities.

We hoped to sneak back in Westfield House the way we'd left, but someone must have seen us crawling along the hedge. The back door banged open on a trio of Moms, who dragged us inside and fetched our actual Moms.

Mom looked mildly confused to be consulted. She held a fan of newspaper clippings. "Twins, go to your room. Our room."

Milly had to be fetched from the parlor, but she accepted being unfairly punished for a crime she didn't commit. We were usually treated as a unit.

On our shared bed, with a threadbare blanket over my head, I tried to convey to Milly the mystery and glory of The Blob. She, selfishly, focused on the part of the narrative where I'd left her behind.

"We'll go back," I said. "It's obvious the perimeter is unguarded after breakfast. We'll hang around the back parlor, and when the kitchen is empty..."

"We're not allowed out of the room," Milly reminded me. She fell on her back and opened that fat island-book by Solzhenitsyn.

I was left with no recourse but the window and its view of the swing set we weren't allowed to use.

There were these bushes that grew against the house. They were pine-ish with flat needles and these fat red berries, like pillows, with a green seed stuck deep in each one like a button. I could lean out over the sill, my hips holding me against the wood, and just reach the berries on the top branches. After much effort, I had collected a dozen, I turned to show Milly, but she was still buried in her stupid book.

"Do you think these are poison?" I asked.

"Oh definitely," she said without looking. "Nothing's eating them."

I squeezed one. Clear gel seeped out, gleaming in the sun. It looked like magic. I ran to the bed and kneed Milly's side until she looked.

Milly scowled at first, but when I demonstrated squeezing fresh gel from a berry she said "Cool!" We spent the better part of the afternoon trying to fill the water glass Becky had left on the bedside table with just the goo, scooping out bits of seed and needle and dirt with one of her makeup brushes.

The goo was sticky and touching it too much clouded the silky translucence. Magic had to be like that—easily ruined. "If I could only get it directly on my bones, maybe it would dissolve them. Then I could be, you know..." I mimed the blob like I had before. I could be more. I could be big.

"The trick is not to kill yourself doing it." Milly didn't ask why I wanted to be a monster. Twin sisters are great like that.

Why did I? Our life wasn't bad, just poor. Not the real poor you see in movies with starving to death and burning matches to survive; the boring kind of poor where you never died of it, but you couldn't eat every day. The kind where you were a Brat and Should Be Grateful.

I was already some kind of monster, just not a very interesting one.

There was a thump from downstairs, and a scream. The scream was our older sister, Becky. The thump was also Becky. I recognized the impact of her body on a wall with sisterly intimacy. There were more screams, more thumps, and a shiver from the walls as though the house had caught cold. A downpour of footsteps tumbled along the wooden halls and stairs.

We could not in these circumstances be judged for breaking our confinement.

Everyone in the Westfield House was in the front hallway, where Mom and Becky were wrestling and screaming, rolling on the ground, banging into the walls, hands in each other's hair. There seemed to be a disagreement on the subject of Becky going out or staying in.

Two women worked to separate them. Another noticed Milly and me and pushed us back from the mob. "Get your family's things," she ordered.

Within minutes, like convicts, we were led out the open front door. The now-familiar brown Buick sat in the drive, the brown woman standing beside it with a weight of personal disappointment. We had failed her. Mom had to be wrestled into the front passenger seat, but Becky got in the back with queenly indifference. As the car pulled away, she was silent beside us, arms crossed, staring in quivering anger at a fixed point on the seat in front of her.

I tried to keep my eyes on the library as long as I could.

#

The brown car stopped in front of our house and Becky took off like a shot with her big tote bag, toward Tallmadge Street. Mom screamed, "Go ahead and go! See if I care!"

Milly and I stayed where we were, holding our breath with the hope that if we were still and silent enough, the brown lady would forget we were in her car and take us home with her.

"You go on with your mother now," the brown lady said.

Just like that, we were dumped back into the ordinary, magic-less world.

Milly and I sat on the sidewalk. There was no reason to go inside. Mom was smacking cabinets, shouting about how unfair it was to get kicked out of a battered women's shelter for being too violent.

"I wish we were battered," I said. "So they'd keep us."

"Yeah." Milly balled her fist and bounced it a few times on her boney thigh.

"You think we could walk back?" I had tried to memorize the path we'd taken, but they didn't let you walk on the freeway, everyone knew that.

Milly wisely changed the subject. "I got a book on witchcraft." She wiped her hands on her corduroys. "Wanna see?"

Well, I could always run away later.

Mom had finished her rant and fallen sobbing into her bedroom, so we tiptoed up to our room, and Milly produced a green, cloth-bound book with a fat "interlibrary loan" sleeve obscuring the cover art.

"Dude, this is so over-due," I breathed in awe.

Milly brushed a reverent hand over the spine. ILL charged way more for overdues than regular books. There was no way we'd be able to pay the fine and get her borrowing privileges back. Milly laid the book open on our bed with admirable calm. "Look." It was full of circle doodles labeled "To Find What Is Lost" or "To Curse a Faithless Lover." I found their intentions sadly non-specific.

"Does any of this work?"

"Not yet," she admitted, and showed me the burned remains of her wealth-attracting ritual at the back of our closet.

I laid down on the bed and Milly drew the Rune of Transformation from page 46 on my back in permanent marker. It felt cold and intensely ticklish, like lines of pure feeling. When I tried to look at it in the mirror, I couldn't twist enough. Milly assured me it looked awesome.

We planned to paint over the design with berry guts, but in the short time that had passed, the goo we'd carefully packed in our grocery bag of belongings had dried into hard yellow snot. Milly wanted to change tactics, but I remembered seeing the same berries down the block.

We picked more of the goo berries, and we smeared them on my skin one at a time. I stood on the back stoop in my training bra and cut offs, freezing in the autumn twilight as the goo dried and flaked off. It felt important that it dried under the moonlight.

The next morning my arms and stomach where I'd wiped my fingers had brushstroke-shaped welts that were warm to touch and stung, but that was my only transformation.

#

No one had really mentioned school while we were at Westfield House, and my teacher claimed never to have heard of it, though I offered to show her which house it was, if she were to drive me to Erie. She sent me to talk to the Vice Principal, instead.

When we got home from school, Mom was on the phone to someone explaining that it wasn't her fault her children were violent and uncontrollable, and they should have let her stay. Becky wasn't home; there was no thumping music coming from her room.

I got the biggest hammer out of the kitchen drawer and laid my hand on the reassuring stone of the back stoop. I pressed the smooth metal head against the fine bones in the middle of my left hand. Remembering past failures at pounding nails, I took a slow practice swing, just kissing the skin. It didn't hurt, which gave me hope. I drew back again and closed my eyes, picturing the arc, the impact. I knew these things hurt less when they were fast. I pulled the hammer back a little more and—

The back door screeched open. "Stop that." Milly took the hammer from me. "You can't get through your whole body. You'll pass out or something before you got to your elbow, and how would you do the other hand?"

"I should start with my feet?"

"No. You don't work magic with physics. They're like opposites." Milly could sure sound authoritative when discussing things she'd never seen work.

Milly took me to the pantry and drew pentagrams in salt on the greasy carpet. Her book said salt was a natural repellant of magic, so you could trap magic in it, like how lines of oil could trap water drops.

Nothing felt magic with the smell of stale carpet and the sun shining on cans of wax beans. Mom was going to flip when she found out Milly wasted her pickling salt. I went out back. Scanning the patchy grass and toy-strewn dirt, my eyes fell on the leaf pile. We'd started raking the other day and gotten tired and left it. That was the story of our lives. The berry goo, the stay at the shelter ... everything that pertained to us was a poor attempt, given up halfway.

This one thing, though, I could fix. I picked up the wet rake and tried to pull the pile into a respectable shape. I wasn't sure what you were supposed to do with a leaf pile after you'd made one. Pick it up, somehow?

I felt something wet and cold brush my ankle. A sickly yellow slug clung to me, right on top of my ankle bruise. It undulated and I felt every detail of its motion with breathless horror. I threw the rake, and it clattered against the tree. I tried to shake the thing off my leg. The slug noticed not at all. I was incandescent with rage. I spun and stomped to fling this horrible thing off me.

"Disgusting. Gross. Ugly. Stupid!" I was dancing in a circle, hurling every insult that had ever fallen on me. I stomped on the rake and broke one of its plastic tines. I thought the destruction would be satisfying, but it wasn't.

I didn't feel the slug disconnect so much as stop caring that I'd felt it at all—my anger was its own thing now, separate and perfect and not a part of the slug. I was an engine shifted into gear and fueled by pure aggression. I demolished the rake. I kicked the leaves. I attacked the tree. I loved that tree but now I wanted to destroy it. Maybe because I loved it. Milly and I, everyone said, were the reason we couldn't have nice things. I didn't deserve to have something to love.

The bark of the old oak felt like brick against my knuckles, bloodying them. I mashed my fists harder into the roughness, but it was like my hands were gummy.

I grabbed the trunk as though to strangle it. My hands spread outward, like syrup pouring, fat and soft and glistening. My stomach lifted inside me, sickness tickling the back of my throat.

My rage melted out of me as my hands melted into bark. I could see the tiny cracks of my palms extending, the familiar road map of veins growing into a landscape. Was I really seeing this? I took a step back, yet my hands stayed where they were. "Milly?" My arms pulled like taffy. They drooped in the middle.

Disgusting, and I feared for my bones, for my nerves, but there was a freedom growing like a laugh in my gut. I didn't have to keep being an awkward girl-shape.

I surged. My hands stayed on the tree, but they didn't stop me moving forward. Leaves came with me, and that was good. I wanted to be messy. I rolled up the side yard, over gas meter and tree roots like a wheel over cogs, and that was what it felt like, like being a tractor tread over soft ground.

My hands pulled off the tree after me, a distant plop of separation. They weren't really hands anymore. I wasn't really me, anymore. I oozed. I quivered. I slid. Guts should be twisting, nerves tearing, but nothing felt wrong. The asbestos shingles on the side of the house with their fake wood pattern felt as comfortable as the twigs and grass and cracked, pebble-filled sidewalk.

I'd unlocked something I always knew was inside. My monster-self. It was limitless. I was growing in size as I picked up debris from the street—a plastic margarine tub, a straw, a super bounce ball. I hit the light pole on the tree lawn head-on because I wanted to feel myself split against it the way the blob in the movie had split against the movie theatre doorway, and I did, and it was awesome. I felt every splinter on the pole drag its imprint into me, every rusty staple and tatter of a lost dog poster. I joined together on the other side with extra bubbles inside like joy.

I pressed my forehead to the street and looked through my attenuating body. The house was wavering behind me. I could see the lump of moss on the porch roof that had once been an orange I'd thrown out of my window.

I did a backflip, well, except I didn't have a back. I flipped, rolling over across the street, picking up gravel and a bit of flattened squirrel. You'd think I would be a big trashy mess, but I was getting clearer, dissolving things into part of me. I was a glorious peach Jell-O color, like one of the shades of sunset it's hard to separate out.

Milly stood in the front door, her mouth open, looking like a mirage as I watched her through my stomach—or my back—I wasn't really sure what way up I was anymore. Where were my eyes? Were they floating like grapes in jello? I rolled toward her, trying to talk, to tell her how wonderful it was, but my lips and tongue flopped and stuck and dragged. I burbled.

I should have remembered about the salt. I did remember, shortly after Milly looked down at the big blue container in her hand. She raised it and then stopped. She frowned, and I could see her temptation to go back inside and let me be, yet another person who had abandoned her.

I reached for her, to take her with me. She could transform, and we would be monsters together. My tendril slipped against her ankle, and I felt all the strength and solidity of her. I pulled hard, and her tendons flexed against my surface, but the flesh resisted, compressing, bruising.

She threw the salt at me. I tasted it on my skin, shocking and hot and—

I burst. I burst like a zit, liquid spattering the screen door, falling in fat drops on the dusty porch floor. I was just myself again, shivering and wet with my legs on the tree lawn and my butt in the street, bare-ass naked. My own sister did this to me.

Milly tossed the empty salt canister aside. "I mean, really."

Academically, I could appreciate her desire to make me normal. There weren't a lot of good jobs for blobs. But would a blob care? I wanted to scream, but all I got was a tight throat and saying, "It... it..."

Milly grabbed my arm to pull me to my feet. "If you did it once, you can do it again."

She didn't know that! I yanked free of her. "I was going to take you with me!"

"Do you want to stay out here naked, then?"

Chastened, I followed her inside. Milly had left her Gulag book on the nubbly, musty old couch blanket. Its spine was a little more curved than before, the crinkly library-protection plastic separating. A tab of torn junk mail stuck out from the sedimentary strata of pages, marking her place. She was nearly done. She slid the book to the side and held the blanket up to me.

The pills and snags of the fake wool blanket felt weird against my wet body. Like that time there weren't any towels, so I used the bath curtain. Milly sat down. I asked, "Don't you want to know how I did it?"

"We've got time." Milly patted the space next to her on the couch. She wasn't budging so I rolled myself into a blanket-burrito and rested my head on her knee. She cracked open the fat doorstop of a book. "What this is really about is how people can be the worst monsters." She cleared her throat and read in an on-the-phone voice, "I dedicate this to all those who did not live to tell it." She shifted her elbow over my head to turn the page. "Chapter one: Arrest." It was nice, listening to the story, getting caught up in it, and I got the message, clear and strong.

Milly and I were going to be such glorious monsters.

© 2025 Marie Vibbert

Marie Vibbert

Marie Vibbert is a Hugo and Nebula finalist with over 90 stories and 3 novels in print. Her works have been translated into Chinese, Czech, and Vietnamese. She fell in love with science fiction when she snuck out of a battered women's shelter and stumbled on a screening of Day the Earth Stood Still in a library basement. This story is a fictionalization of that event. Learn more about her at marievibbert.com.